This overview introduces key terms, historical foundations, and commonly asked questions about Beta Israel religious life. It is a living document and intended to serve as a starting point for deeper study.

Beta Israel is a longstanding Jewish community whose oral tradition traces continuity to the First Temple period. For centuries, Jewish life was sustained in the highland regions of northern Ethiopia under the religious authority of Kessim (religious leaders) and shimaglae (elders). Rooted in the textual tradition of the Orit, religious life was preserved through oral transmission and shaped by sacred text, communal memory, and covenantal practice which continues to echo today in Israel and across the diaspora.

The term “Beta Israel” (literally “House of Israel”) refers to the historic Ethiopian Jewish community and its traditional religious framework. “Ethiopian Jews” is a broader contemporary term used especially in Israel and the diaspora. While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, “Beta Israel” more precisely names the historic community and its religious structure.

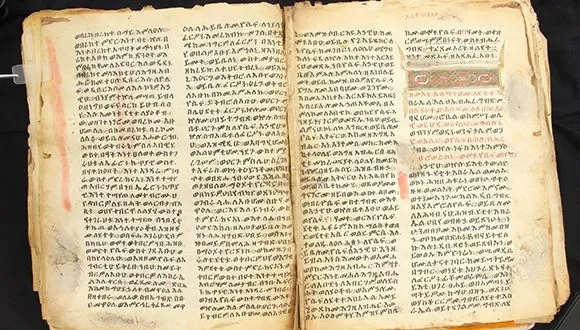

The Orit is the central sacred scripture of the Beta Israel tradition.Most strictly, the Orit refers to the Five Books of Moses (the Torah), preserved in Ge’ez, an ancient Ethiopian liturgical language. In religious life, these texts are transmitted alongside the books of Joshua, Judges, and Ruth, which are also part of the traditional scriptural corpus. The Orit functions as the primary source of religious authority. Kessim interpret and teach from these texts, guiding Shabbat observance, holiday services, dietary practice, and communal life.

FAQ & Key Terms

1.What is the Orit?

Picture: Rare 15th century copy of the Orit recorded by TAU's Orit Guardians program. Kept by Beta Israel now to be digitized by the program at TAU.

2.Do Beta Israel follow the Talmud?

Traditional Beta Israel religious life developed outside the rabbinic acadmies of the Land of Israel and Babylonia. As rabbinic Judaism codified legal interpretation in the Mishnah and Talmud, Beta Israel communities preserved Jewish life through the Orit, oral transmission, and the leadership of Kessim. For this reason, traditional Beta Israel practice does not center the Talmud as binding legal authority. Instead, religious observance is rooted directly in the Torah and Orit as preserved and interpreted within the community's religious leadership across generations, reflecting a distinct historical development within Judaism. In contemporary contexts, especially following migration to Israel, most Ethiopian Jews now practice within rabbinic frameworks, while navigating the relationship between inherited Beta Israel tradition and broader halakhic norms

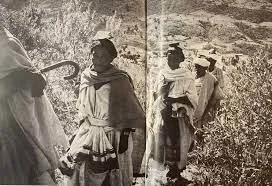

3.What is the traditional Beta Israel holiday cycle?

Traditional Beta Israel observance centers the biblical festival cycle described in the Torah, alongside communal observances such as Sigd. Biblical festival cycle include: Shabbat, Rosh Chodesh, Passover, Shavuot, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Shemini Atzeret. Because this tradition developed outside the rabbinic framework, holidays that emerged within rabbinic history were not historically part of Beta Israel religious life. This reflects preservation of the biblical festival structure within a distinct historical pathway.

Picture: Women carrying stones on their heads to where Sigd is celebrated. Ambober, Ethiopia, 1984. Photographer: Joan Roth

4. Are Kessim and Rabbis the same?

Kessim and rabbis both serve as religious leaders, but their roles developed within different historical frameworks. In the Beta Israel tradition, Kessim are spiritual leaders, teachers, and interpreters of sacred law. They guide prayer, oversee life-cycle events, preserve ritual practice, and transmit religious knowledge within the community. Rabbinic authority developed after the destruction of the Second Temple and is rooted in the study and interpretation of the Torah and Talmud. Kessim historically derive authority from mastery of the Orit, oral transmission, and communal recognition. Their leadership reflects a priestly and text-centered and community rooted structure rather than the rabbinic legal system that developed elsewhere.

Kessim at Sigd event in Jerusalem, 2022

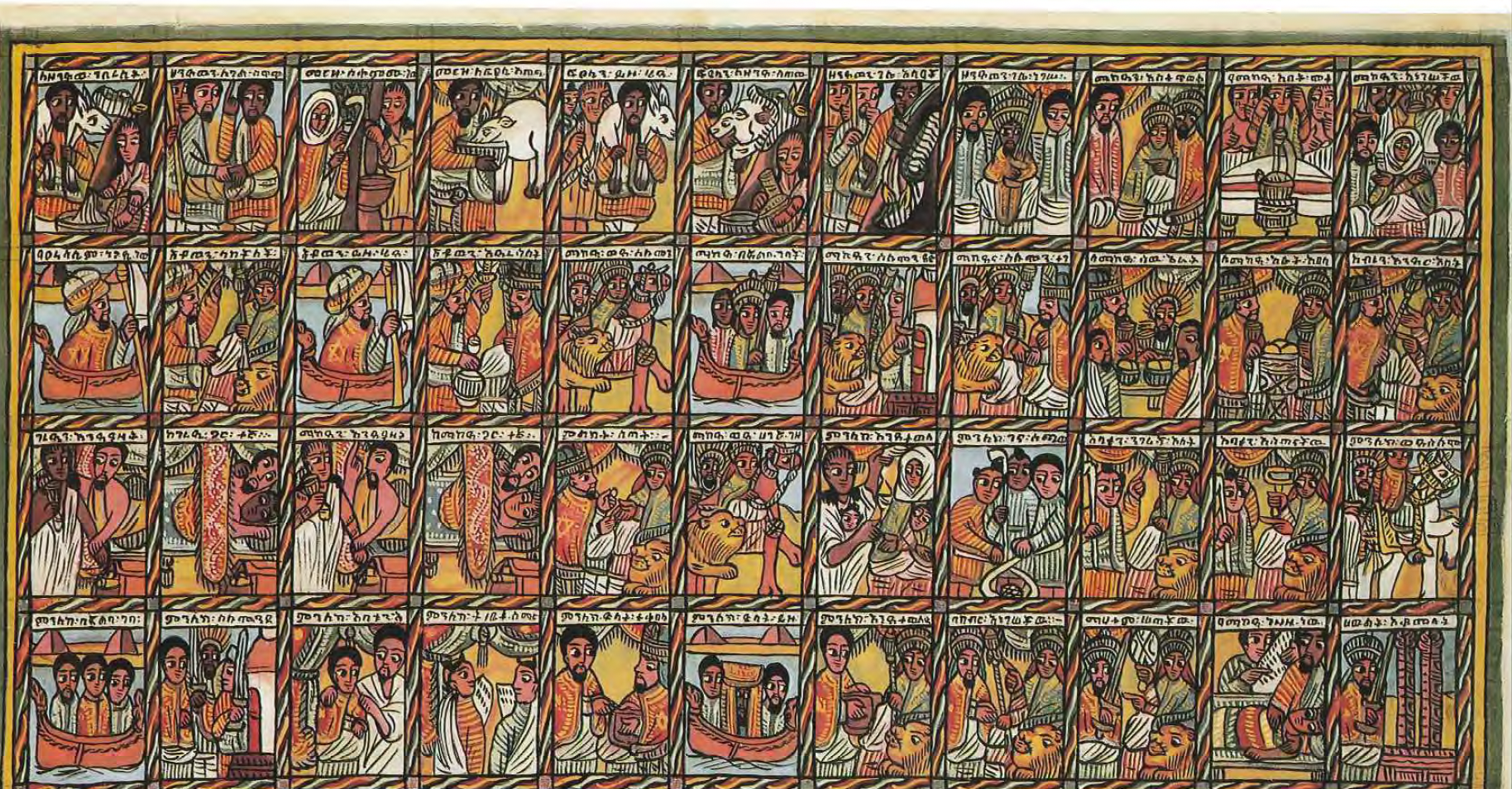

5.Where does Ethiopian Jewish history begin?

Ethiopian Jewish tradition traces its continuity to the era of King Solomon, as preserved in the Kebra Nagast. The Kebra Nagast is not a book of Jewish law, it’s the national epic of Ethiopia, blending history, folklore, theology, and cultural memory. It recounts the story of Makeda (the Queen of Sheba), her encounter with King Solomon, and the birth of their son Menelik I, who in Ethiopian tradition becomes the founding figure of the Solomonic dynasty. The narrative also includes Makeda’s acceptance of Judaism, the transfer of the Ark of the Covenant to Ethiopia and affirms a covenantal connection between Jerusalem and Ethiopia. The importance of this tradition is in its theological and geographical meanings which express a longstanding understanding of covenantal continuity and spiritual linkage between Ethiopia and Jerusalem.

Picture: From Beta Israel A House Divided, nacoej.org Above: Painting by Jannbaru Wandemmu depicts popular Ethiopian legend of King Solomon and Makeda, the Queen of Sheba. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia